If angst plays havoc with us as adults, then a baby should be a horrified, quivering mass of flesh, right? On the contrary, a baby has no angst at all. It doesn't know what angst is.

A baby is not aware of anyone else in the world. In its opinion, it is the world. It isn't the center of the universe. It is the universe. When it closes its eyes, the world disappears. When it opens its eyes, it recreates the world. A baby is totally self-absorbed. It has little concern for anything else except oxygen, water, food, and freedom from pain and extremes of temperature. The fancy words for this state of infantile affairs is primary narcissism, total self-love.

The baby's central nervous system rapidly develops in the first few months. At about one year to one-and-a-half years of age the baby gets broadsided by the dread. It begins to perceive that it is not the world; it is not the universe. The angst begins to creep and then flow into the baby's psyche. It begins to search for its identity and its sense of somebodiness. And who does it turn to? Mom or whomever it is that plays the mother role.

As Dr. T often says, I can hear the wheels turning in some of your brains. He's going to lay the blame for all of the problems in the world at the feet of women who are mothers. No, I am not. It just happens that Mom is the traditional one who is around and meeting the baby's needs when the baby is becoming aware. If the dad is the primary caregiver, then he is the one who becomes the most powerful shaping force to whom the baby turns. But usually, Old Hairy Legs is just a blur to the baby, rushing in and out of its fledgling life, busy with the car, the lawn, sports, or the job. This is changing for many dads. They are getting to know the joys they've usually missed. The less than responsible dads are satisfying their selfish goals and missing a delightful experience. That's too bad.

Whoever the primary caregiver or mothering-person is, the baby totally depends upon this person. This is the first person to tell the baby what will make it worthy of attention, acceptance, and the resources it needs to be a unique individual, distinct and special from all others.

How do we know what makes us worthy though?

I started gathering my worthies from a lady called Eloise and a guy named Tom, Sr. An older lady I knew as Maman contributed to my collection of worthies, too. Then a fellow ten months younger than me, who people called John, entered the world followed by a succession of others. Their names are Mary Margaret, Catherine Ann, Teresa Louise, Patrick Joseph, and Paul Jude. But these people were smaller than me and were taking up a lot of attention from the big guys I had known much longer than they.

Our SO's messages of worthiness were very powerful. These messages were so powerful that they run our lives as adults whether we are aware of them or not. They are the personal principles by which we live. They are the prime directive for all we do.

Why are they so powerful? The reason is that we learned these messages with a child's mind. Here are three of the more important reasons these messages stick with us. First, we learned these messages when we knew nothing at all. Our minds were as blank slates, a tabla rasa upon which nothing had been written. Because of this, we had no prior messages that could conflict with these first messages. We had nothing with which to challenge the validity and reliability of the messages we received.

Secondly, we depended upon the SO's for our existence. We had no way of knowing whether or not they would care for us. If we did what they said and acted in the ways they told us, then we would get more attention, affection, and resources, right? It seemed to make sense to us. Like Bill Cosby said, "I brought you into this world and I can take you out of it."

The third reason these early messages of worthiness were and are so powerful involves the apparatus with which we learned them. Our little minds dealt with messages in a concrete fashion. The simplicity of our perception told us that what the SOs said is what the SOs meant ; no ifs, ands, or buts. Our vocabulary and ability to deal with abstractions was limited. The subtle meanings that may have been intended escaped us. When we heard, "I could just kill you for doing that!", we knew we were being sentenced to death and crouched in the corner waiting for the executioner.

The lack of conflicting messages, our dependent state of existence, and the concrete simplicity of our minds chipped these messages in to stone. This is why our SOs' messages carried such weight and stay with us until we pass from this world.

"People like us aren't pushy."

"You should share with other people."

"It's not nice to talk behind people's backs."

"Don't hit girls."

"Pick on somebody your own size."

"Don't tattle on your little brother."

"Pick up after yourself."

"Don't use other people's things without permission."

"Set a good example."

"Big boys don't cry."

"Never tell a lie."

"Don't put off 'til tomorrow something you can do today."

"Clean your plate, because people in India are starving."

"Always mind your elders."

"Don't talk back to me."

"Always be on time; never be late."

"It is better to give than to receive."

"Cleanliness is next to godliness."

"Treat people the way you would like to be treated."

I probably heard many more, but these are the ones I can remember. You may recognize some of these messages within your life. It's important to remember that these messages were received with differing degrees of emphasis.

Internalization wove my early messages into a tapestry of learned needs that defined the person I had to be in order to feel worthy. This was the period of time in which my personality solidified. This was when my prime motivations were set for the rest of my life. This was when I really became unique and distinct from all others who had been, who were, and who would ever be.

The uniqueness I had acquired set me apart from my brothers and sisters while they were becoming set apart from me. It would seem that because my parents' offspring grew up in the same house, in the same environment, with the same SO's that we would develop the same or similar personalities. On the contrary, the environment into which I was born was different than the environment into which my brother, John, was born which was different than the environment into which the rest of my brothers and sisters were born. When I was born, my environment consisted of a 28-year-old father and a 23-year-old mother who were married for less than a year (but over nine months, I must say) and who had never had a child. By the time my youngest brother, Paul, was born, his environment didn't resemble the environment in which I had started life. Eleven years had past. Six other children occupied the house. Our grandmother was living with us. Etc., etc. etc.

Certainly, my brothers, sisters, and I share some common values and traits. But our personalities are unique and distinct. The messages I heard when I was growing up were different than the messages Paul heard. My parents were struggling, learning about one another, and being careful not to break me. Paul's parents had seen it all when it came to kids. They were more experienced. They were still struggling, but were not as anxious about it. And they weren't as afraid of breaking Paul.

Our development, our worthies, our early messages, and the process of internalization make us different. Each of us are more than different than one another; each of us is unique. No one has ever existed, exists now, nor will exist again who is just like you. No one has ever existed, exists now, nor will exist again who is just like me. No one has ever existed, exists now, nor will exist again who is just like any other person.

Learned needs are normally distributed among the population. Most people have an average degree of strength for each of the learned needs. But individually, each of us has a unique set of learned needs. This means your learned needs are different than mine and my learned needs are different than everyone else's.

This quality of uniqueness is very important. Our uniqueness developed in the ways we received the messages. Though we may have heard the same early messages, the messages were conveyed to us with different frequencies and intensities . For example, you and a guy named Fred may have heard from your parents that you should "be kind to others". Your parents may have shared this way of acting and thinking with you every morning of your early life. If your parents went even further and reinforced the message with small rewards every time you were kind to your little sister, the message could be fairly strong in you.

But Fred may not have heard the same message the way you did. Fred may have heard "be kind to others" only three or four times a year. His parents may have assumed actions speak louder than words and didn't talk that much to Fred about "being kind." On top of that, let's say Fred didn't have any brothers or sisters upon whom to practice this way of being worthy. As a result, Fred had few opportunities to be reinforced with a pat on the back, an ice cream cone, or a smile across the room. Fred's message is there, but compared to yours, it wouldn't be very strong.

We can summarize some of the major learned needs that seem prevalent in the population. In this discussion, we won't spend too much time explaining all the possible learned needs. We won't define the learned needs in minute detail either. You can find more comprehensive and scientific discussions in books and research journals devoted to personality theory. A simple explanation of how learned needs work and why they are so powerful in everyday life is our goal.

Below are some of the major learned needs and their common definitions. I've include examples to clarify what they mean and what messages may have spawned them.

Dominance is the need to see oneself and be seen by others as Number One, King of the Mountain, The Guy or Gal in Charge, The Person with Control, The Leader of the Pack, and Top Dog. A person with a high need for dominance may have received an early message like "I will consider you worthy if you are number one in everything you do. You've gotta be in charge." A person with a low need for dominance may have heard "People that are pushy are common."

Achievement is the need to see oneself and be seen by others as someone who does his or her very best regardless of the rewards and payoffs. A high need for achievement may have grown from a messages like "Anything worth doing is worth doing well", "I will not consider you worthy unless you always and everywhere do your best", and "Everything you do must be done perfectly. Then I expect you to rapidly improve." Someone with a low need could have heard, "Winning isn't everything." or "Few things matter so much that you have to do your best at all times."

Succor is a learned need that suggests that a person and others will consider him worthy if he empathizes with the plight of others, helps them when they need it (and don't need it), and nutures them as much as he can. A high need to give succor may have developed from an early message like "It is better to give than to receive." A low need may have been rooted in the messages, "People don't like charity" or "It's better not to get involved."

Order, also read as predictability, is the need to feel and be seen by others as being prepared for what will happen next or to have a minimal level of chaos and change in one's life. This need is also reflected in the deep desire to have things well-organized, to have a plan and a purpose for everything done. A high need for order may have come from the message, "Always be prepared for tomorrow," while a low need may have grown from "A little chaos makes life an exciting adventure."

Independence is the need to see oneself and be seen by others as someone who needs no one, no how, at no time. A person with a high need for independence may have heard, "Being self-reliant is better than having to depend on others who will eventually disappoint you." A low need may have risen from the message, "It's better to collaborate with others when you need to get something done."

Dependence suggests that a person needs to see himself and be seen by others as someone who needs other people, otherwise he'll feel less than worthy. A person with a high need for dependence may have heard something like "People who need people are the luckiest people in the world" or "It's a good thing to have to rely on the people close to you." A low need could be the result of the message, "If you learn to fend for yourself and make your own decisions, I will consider you to be a competent, well-adjusted human being."

Regarding independence and dependence, a time-out is probably required. You may think that these needs are either-or in nature. Either a person has a high need for independence or a low need for independence. And if he has a low need for independence, then he's obviously dependent. We separate the two because there are people who need to feel independent in some parts of their lives and dependent in others.

For instance, an executive of a large company may have a high need for independence when it comes to business or professional issues. He or she may not want advice from anyone. This person may want to be seen as someone who makes decisions using his or her own resources.

However, when it comes to emotional issues, this same executive could also be very dependent. The executive may call his or her mother to discuss how to handle last night's argument with the spouse. He or she may turn to a tight group of friends to get the emotional support absent in the work place.

The needs for independence and dependence often cause conflict for people. From time to time a person can find himself in a situation where he needs to be seen as independent in the eyes of others. At the same time, the person may have a gnawing feeling that he needs these same people to get what he needs. This conflict can be disastrous. It can lead to procrastination at the expense of others, alcoholism and drug abuse, ulcers, heart problems and stress headaches, and the most destructive of all, suicide. This is the reason we have constructed two continuums, one for independence and another for dependence.

Group Approval is the need to perceive oneself and be perceived by others as worthy of approval from groups of people who matter to that person. The messages that may have led to a high need for group approval may have been, "Don't upset other people. You need to be well liked to get what you want from life." A low need may have emerged from messages like "It's most important what you think about yourself. Others' opinions of you don't matter at all."

Affiliation is the need to see oneself and be seen by others as a person who belongs; as a person who is a part of something or is known to associate with people considered worthy. A person with a high need for affiliation may have heard, "Always hang out with people who you want to be like one day. Their success could rub off on you." A low need for affiliation might come from messages like the Simon and Garfunkel song declaring, "I am a rock. I am an island." A low need person may have learned that solitary pursuits or being a lone-wolf is a very worthy way to be.

"Right" is the need to feel and be seen as the person who has all of the answers, knows everything about every topic, and is never wrong. A person with a high need to be "right" could have grown up in a household like Joe Kennedy, Sr's. Papa Joe would require the little Kennedys to prepare each day for a current events conversation at the family dinner table. At the nightly gathering, he would turn to each child and ask about the political races in who-knows-where, the coal mine strikes in who-could-care-less, or the coup d' etat in what's-its-name republic. If little Joe, Jr., JFK, RFK, Eunice, Kathleen, or Teddy didn't have the right answer, he or she was admonished and held up to ridicule before his or her siblings. But someone who lived in a house like mine may have learned that it was okay to make mistakes. Furthermore, if you admit to your mistakes, people would respect you even more.

Honesty is the need to feel and been seen by others as a person of the utmost integrity; one who never lies; someone who can be depended upon to tell the truth in all circumstances. A person with a high need for honesty may have heard "Honesty is the best policy" or "Lies are an abomination in the eyes of God." A low need for honesty could have stemmed from the message "Don't ever let someone know what you're thinking. People will use it against you" or "To keep from hurting people's feeling sometimes you have to tell a little white lie."

Perseverance is the need to feel and be seen by others as a person who picks himself up when down, who won't give up, and who strives to reach a goal no matter the obstacles. A person with a high need may have heard, "Get up and try again" or "Big boys don't cry" or "Don't let anything get in your way" or "Winners never quit; quitters never win." A person with a low need could have heard, "Know when you're beating your head against the wall" or "It takes more courage to walk away from a fight."

A second point involves the possible messages that give birth to these learned needs. Some early messages we receive are not in the form of verbal criticism, oral admonitions, spoken praise, and words of advice. It's not just the words we heard that impact us. We also observed our significant others' behaviors. We paid attention to the little, and especially the big, things our parents, siblings, peers, and other important people did. Sometimes these messages were more powerful than any words we heard. We witnessed affection in our homes, saw how arguments were handled, watched people deal with conflict, and observed people nuturing one another. These messages transmitted what would be considered worthy just as surely as if dad or mom sat us down and said these things to us.

After I learned about learned needs and some of the other principles of behavior, I started paying closer attention to what I did and said and how I reacted emotionally in different situations. For instance, when I was in a group of people I didn't know, I noticed that I would stand off to the side and wait until someone approached me. I thought about how I felt in that situation and discovered that I didn't feel terribly uncomfortable. With this and other evidence, I surmised that I got along pretty well in new situations with new people.

All this paying attention to myself and what I was doing I call "self" experiments. I spent a lot of time noticing what I did and said and how I felt in all kinds of situations. My question was simple, "What learned need or needs are operating in this situation?" I asked this question of myself when I was in meetings, when I dealt with my boss, when I worked with others, when I had to discipline people, when I was put in charge of something, when I made mistakes, when I treated someone unfairly, and a host of other common circumstances. I would ask others for feedback to see how I was coming across to them. I would even try out different behaviors that I had never tried before. My "self" experiments were interesting, revealing, and downright fun. I still challenge myself in these little ways, pay attention to how feel, and approximate my learned need structure.

But in the end, you and I will never know exactly what our learned needs are. We can spend the rest of our lives in our search of our "selfs." Sure, we can spend years going couch- diving and wig-picking with psychoanalysts, counselors, and therapy groups. Unless we cannot function effectively in the world or have catastrophic problems with which few people could deal, the costs far outweigh the benefits. Besides the self-discovery process is thrilling.

It can be scary to some of us because we might find out we aren't such wonderful people. If you are among the apprehensive, I encourage you to try your own "self" experiments. Approach them with an appreciation that you need your seeming weaknesses as well as your apparent strengths to be who you are. With even a rudimentary approximation of your learned needs, you are better able to select your behaviors with an adult's mind instead of relying on your childlike autopilot.

I personally believe there are at least five billion different kinds of personality. And if we include everyone who ever lived and all those who are yet to come, we'd probably find that many more personality types. It's helpful to put people into groups to understand general features and make simple to complex predictions about them. This is the reason for personality theories. But as helpful as they can be, they can be very harmful to people as well. We'll explore the downside shortly.

Now here's the downside of these instruments, tests, questionnaires, and surveys and their associated theories. The labels generated from each approach may suggest to you and me that we are doomed to behave in certain ways. They could suggest that we cannot control our behaviors, and therefore, are not responsible for what we do. In untrained hands, the labels and results could lead others to believe that they don't need to get to know us because the results tell them everything they need to know about us.

I want to relate an incident in which a friend of mine found herself. I was involved. I want to tell you this story because it demonstrates how questionnaires and surveys and the labels they generate are dangerous in the hands of the wrong people. My friend, I'll call her Rita, was looking for a job after having taken four years off to spend time with her baby boy. Rita wasn't sure what kind of work she wanted to do. She decided to take a battery of personality profiles and interest surveys to discover the types of jobs she might like and for which she would be suited. Rita went to a consulting firm that held a franchise with a psychological testing group and sold these tests to people looking into career possibilities. She took the tests.

Rita got a phone call from one of the counselors and set up an appointment to review her results. At the beginning of the conference, the counselor pulled out the Rita's results and began telling her that she wasn't suited to work in this job or that. The counselor told her that based on her results she should not even be married nor should she be raising a child. When Rita challenged the counselor's assessment, the counselor became defensive and retorted, "These instruments have been extensively tested for validity and reliability. They are never wrong. They measure what they intend to measure. If you took them again, we would get the same results. I know it's probably hard for you to accept this. Many people have some sort of problem with what we discover and disagree with their results. Your answers to the questions say that you are a cold, distant person, you exhibit behaviors that are dysfunctional, and you could be a candidate for alcohol or drug abuse. You'll simply have to accept the fact that this is the way you are."

Completely disheartened, Rita went home and did not leave her house for weeks. Her husband also challenged the results of the instruments and encouraged her to get on with her job search. His attempts were fruitless. Rita resisted any of his suggestions. She rejected all of his encouragement. She sunk deeper and deeper into a sense of worhtlessness. She became uncommunicative. Her marriage began to suffer. Eventually she agreed with her husband to go with him to a marriage counselor.

The marriage counselor immediately identified what was going on in their marriage. The counselor reviewed the results of the psychological tests, surveys, and questionnaires with the Rita. Instead of interpreting the results from a negative point of view, the counselor identified the positive aspects of the traits identified. The counselor went even further by discussing the meanings behind the labels. She asked Rita why she had answered certain questions in the way she had and sought a deeper understanding of Rita, not the tests.

Rita began to see that if the results were read one way and if she concentrated on only a few items, she certainly had little to look forward to. However, she found that she could not be weighed and found wanting based on her answers alone. She understood that zeroing-in on only one or two or three traits exclusively gave her a limited view of herself. She discovered many more possibilities by viewing all of her psychological needs simultaneously as an integrated whole. She learned that a few simplistic labels hardly began to describe the complex person that she was.

My purpose is not to trash psychological instruments, personality tests, and the other methods. These tools are useful aids to discover our motivations, learned needs, worthies, and ways and means of feeling like somebody in this world. These approaches help us gain valuable insights about ourselves and others. They promote self-awareness. They offer possible explanations for the paths we have chosen to travel in life. They alert us to untapped resources in ourselves we may have ignored, conscientiously or unconsciously. No, I am not prepared to trash anything assisting us in our quest of self-discovery.

However, I am prepared to suggest that we may over-use these methods. We may over-rely on them. We may interpret them inaccurately and inappropriately. We may place too much emphasis on them. We may put too much faith in them. Earlier we reviewed the differences between principles and techniques, toolboxes and tools. These psychological devices are tools, techniques. With these particular techniques, we constantly run the risk of learning how to use these hammers and seeing every problem as a nail. People are not nails.

Secondly, this sense of self gives us a predictable foundation for our lives. By defining what is important and unimportant to us we can plan and organize what we will and won't do without thinking about it. If we didn't have a sense of self, we would confuse ourselves and others. We wouldn't know what to expect from ourselves and others. Life with others would be awfully chaotic.

Third, the self identifies who we are and who we need to feel like in order to feel worthy. It also sets us apart from every other human being. It lets us know what we have to do to reduce the amount of angst we sense and helps us select the behaviors that will work for us.

Finally, the number one job of every human being is the protection and enhancement of his or her sense of self. Everything we do, everything we think, and everything we say is directed toward this job. It is that simple.

Violation of the Self

Throughout our lives we and others violate our sense of self. When you violate your sense of self, you punish yourself. You either feel guilt or anxiety. These result because you didn't do the things that you needed to do to meet your real needs. For some reason you did not live up to the somebody you gotta to feel like.

If someone else violates your sense of self, you react defensively. Because that person has threatened the somebody you have got to feel like or has made you feel like less than somebody, you need to do what you can to protect your "self" from these real or perceived attacks. Sometimes your reactions are effective and productive and you re-establish the somebody you need to feel like. Other times the attacks are so devastating you may not recover completely.

Please note that defensive actions include many more behaviors than just counterattacks and retaliations. You may defend your "self" by trying to understand the other person's point of view. You may ignore the threats. You may run away. You may buckle under and take the punches. Whatever behaviors you use will depend on the situation, your learned needs affected, and the relative strength of the learned needs in question. For instance, if someone accused you of lying and your need to be seen as honest is very high, you might fiercely defend yourself to the death. If your need for honesty is average, you might be offended, but you would not dwell on the accusation very long and eventually forget it. And if your need was low, you might be a little tickled that you were found out and say to yourself, "If he only knew the real truth."

I was discovering this information while working toward my MBA. My low need for dominance didn't seem compatible with the aggressiveness preached in the MBA program. In fact, the things I learned in management, marketing, economics, and other courses offended the somebody I had to feel like. For weeks I struggled with this conflict. I began to think that I had made a huge mistake by studying about the business world.

I remember sitting in the backyard with my dad, upset with myself and my choices. I was a mess. Dad listened to my concerns and asked me how I had, all of a sudden, gotten concerned about myself. I explained the conflict and gave him the history of the previous few weeks. Dad in his wisdom pointed out that focusing on only one feature of my personality was dangerous. He recounted the successes in business I had had before I went back to school. He showed me that it was because of my very low need for dominance, combined with my other needs, that I was successful. But what really helped me was his reminding of what Dr. Timmons had said: "We have to distinguish between our real needs and our ought needs."

Ought needs are ways of behaving in certain roles that are apparently effective on the average. You have heard ought needs quite a bit as you've traveled through life. If you're a salesperson, you ought to be assertive, even aggressive. If you're an executive, you ought to be dominant and in control. If you're a nurse, you ought to be caring and helpful. If you're a scientist, you ought to be rational and empirical. If you're a mother, you ought to be protective and nuturing. If you're a preacher, you ought to be reverent and pious. Every culture has a list of oughts. Every role we could assume in life has prescriptions and proscriptions designed to define the kind of persons we should be to be effective in those roles. These ought needs offer the the guidelines and rules by which we should play our occupational and avocational games.

Ought needs influence us and are important, but they are not our learned needs, our real needs. Our real needs define the somebody we've gotta feel like. The operative word is gotta. Ought needs define the somebody we should feel or be like. Gotta is a lot stronger. It means we have no choice about what it is that will make us feel worthy. As we're discovering our learned needs, we may confuse what we ought to feel with what we've gotta feel.

Maybe this horse is dead, but I'm going to beat it a little more until the medical examiner signs its death certificate. Let's say our friend, Fred, is a doctor. He works in the emergency room of a city hospital. He loves his job, but he is always stressed-out. He comes home every night worn-out and emotionally drained. Fred knows he can't go on like this and wants to find some way out.

Now here's some information about our friend we can't readily and easily know. Fred's learned need structure includes a very high need to see himself and be seen by others as a person who is helpful and empathizes with the plight of others, a high need for succor. This is one of his real needs.

His ought need is to be detached and emotionally distant. This is the general code of emergency room personnel. This unwritten code reads, "If you get too close to the patient or the patient's family, you can't do your job effectively and you'll go crazy." Fred tries to live by this code, but it isn't working for him. Every time he tries to ignore a patient's family, his stomach ties itself in knots. When he thinks he has become sufficiently callous, he feels guilty. If he plays the game by the code, he feels like less than somebody. His real need conflicts with his ought need.

As you explore your learned need structure, as you discover the somebody you have gotta feel like, as you go about "self" experimenting, and as you try to identify the "self" you must protect and enhance, you will want to distinguish your real needs from your ought needs. Your real needs will generate guilt, anxiety, or defensiveness if they are violated. If your ought needs are violated, you could feel these same feelings, but not with the strength, pain, and sharpness that real needs elicit. Ought needs are easy to find; real needs are harder to come by.

Learned needs and their degrees of strength simply are. They are not good or bad, right or wrong. My low need for dominance works great when I play sports. When the coach gives me directions, I won't argue with him; I'll simply do what he says. But elect me to president of your club and I would have to struggle with my need to see myself and to be seen by others as someone who lets others be number one.

However, without a doubt, heredity and genetics influence, if not determine, many factors in our personalities. Dr. Timmons called these factors indirect determinants of behavior. Nifty title, eh? Gender, race, skin color, latent intelligence, body build, body size, the reactivity of the central nervous system, and temperament are among the inherited and genetic factors contributing to who we are and who we become. Knowing Lucy's heredity doesn't help us predict what she will do at a football game when a cup of ice is thrown in her lap. We also can't guess what Harry will say when someone steps on his toe because we have a detailed picture of his genetic code. At best, genetics and heredity have a minimal affect on the behaviors of individual's. They certainly contribute, but only indirectly.

Dr. Timmons tells a wonderful story related to the nature-nuture controversy. He worked in a hospital with a group of medical students. One day he overheard an argument between them. One side proposed that the environment determined someone's personality. The other side argued that a person comes into the world with a personality and simply reacts to his or her environment. Timmons interrupted them and proposed an experiment. Both sides agreed.

Timmons and the students walked to the maternity ward and nursery. He asked the head nurse to scrounge up a very dirty diaper and put it in a bed pan. With diaper, clipboard, and pen in tow, he approached the people viewing the babies in the nursery. Here's how the experiment went.

He went up to the first person and said, "Could you help me? We are able to measure many things such as sounds, temperature, and air quality. But until now, we have not been able to measure the strength of smells. We believe we have developed a device that will do this, but we have not calibrated it yet. To calibrate the machine, we decided to asked people to smell something and rate it on a scale from one to ten: one being least pungent; ten most pungent. Would you smell this little boy's diaper and rate it please?"

The person would take a sniff and give his or her rating. Timmons then took the diaper to the next person and said, "Could you help me? We are able to measure many things such as sounds, temperature, and air quality. But until now, we have not been able to measure the strength of smells. We believe we have developed a device that will do this, but we have not calibrated it yet. To calibrate the machine, we decided to asked people to smell something and rate it on a scale from one to ten: one being least pungent; ten most pungent. Would you smell this little girl's diaper and rate it please?"

This person would take a sniff and give his or her rating. Timmons repeated this scenario a number of times, alternating the script between "little boy's diaper" and "little girl's diaper." The only word he changed in his script was boy and girl. Guess whose diaper was rated more pungent? Right you are. The little boy's diaper was rated higher, even though the diaper was the same. The experiment isn't perfect, but it proves a point.

As soon as a baby pops into this world, those in attendance check his or her sexual equipment and behave in ways the culture promotes. Little boys get the blue tags; little girls are pretty in pink blankets. Little boys get the rough and tumble treatment; little girls get the soft and tender touch. Little boys will be football players; little girls should get the dolls. Messages like these die hard, if they can die at all.

So, is it nature or nuture that determines a person's personality? Yep!

CHARTING LEARNED NEEDS AND ZIG ZAGS

You probably had fun with an imaginary friend when you were a little person, right? Let's have a little fun again and create a friend, Jeff. We'll also pretend that we are mind-readers and can look right through this person and see his learned needs, the somebody he has got to feel like, and the sense of self he has to protect and enhance. In addition, we know the early messages Jeff received from his imaginary significant others and how he internalized these early messages. Furthermore, we know the strength of each learned need he acquired and how he goes about meeting them.

Just think for a moment just how powerful you or I would be if we knew all of this about ourselves and people with whom we must work and play. We could really know what makes people tick. We could push here and pull there and prod and goad and urge and encourage others to do almost anything we wanted them to. But you can't, I can't, no one can, so we must pretend.

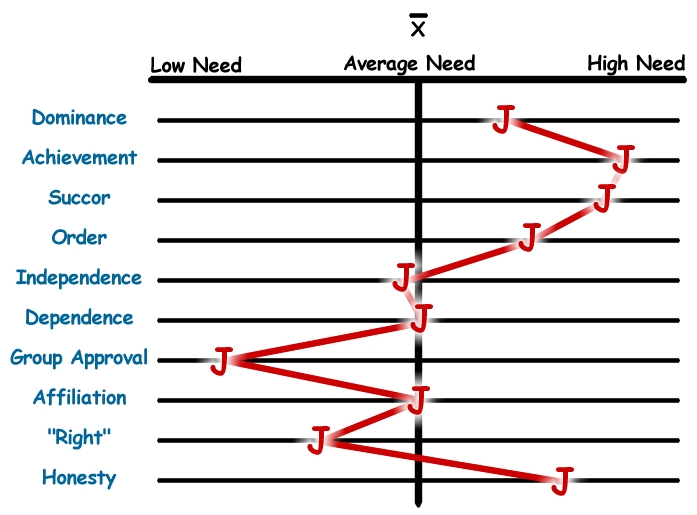

This is how we'll build the picture and graph Jeff's learned needs. We'll list ten learned needs in a column on the left-hand side of the page. We could list more, but ten will serve our purposes. Next to each listing is a line representing the possible range of strengths of the needs found in the general population. If Jeff has a need with a relatively low strength in comparison to the overall population, we'll plot it on the left. If he has a need with a relatively high strength in comparison to the overall population, we'll plot it on the right. And if he has a need that is average, we'll plot it near the middle of the graph.. Then we'll connect the dots and this will be Jeff's unique learned need structure.

The result of our graphing and dot-connecting is a zig zag line. No one else in the world has a zig zag line like Jeff's. Absolutely, nobody. This zig zag is Jeff's self. It is the somebody he has got to feel like. It is the sense of self he must protect and enhance. It is the set of learned needs Jeff must live by. It is how Jeff must see himself to feel worthy. It is how Jeff must be seen by others to feel worthy. If Jeff violates his zig zag, he will punish himself with guilt and anxiety. If you or I violate Jeff's zig zag, he will defend it. It defines who Jeff is.

Learned needs within our zig zags interact and mesh together to form the self. They do not exist separately from one another. They don't operate independently. Learned needs push and pull on one another to produce an amazing array of behaviors that will satisfy them and will enhance and protect them collectively. Therefore, no one learned need is more important than another.

When we try to explain why Jeff does what he does, we must view his whole zig zag. For instance, when Jeff went to college, he did very well in his classes, he joined a scholastic fraternity, and was elected president of his club. It would be very tempting to say that he did well in his classes because he had a high need for achievement. We might assume that he joined the fraternity because he had an average need for affiliation. We lead ourselves to believe he became president because he had an above average need for dominance. If we were to attribute these behaviors to these learned needs solely, we could be wrong.

Perhaps when we talk to Jeff we find out he did well in school because he promised his parents he would do well. If he broke that promise, he would see himself and be seen by his parents as dishonest and that would be just awful. It looks like he is responding to the need to be seen as honest, doesn't it? His need for achievement is probably operating as well, but it isn't the only reason for making good grades.

As for joining the fraternity, Jeff might tell us he saw this as an opportunity to help others because the club ran a literacy program at the local community center. Oops! It might not be his average need for affiliation afterall, but rather his high need to provide succor.

And when he became president of the club, we may find out that Jeff missed two meetings, the one to nominate candidates and the second that elected him. In this case, he became president, not because of any learned needs, but because of events of which he was not aware.

Our zig zags are integrally related. Focusing on one or two learned needs cannot begin to explain our behaviors. It would be convenient if we could, but zig zags don't operate this simply. Too bad, eh?

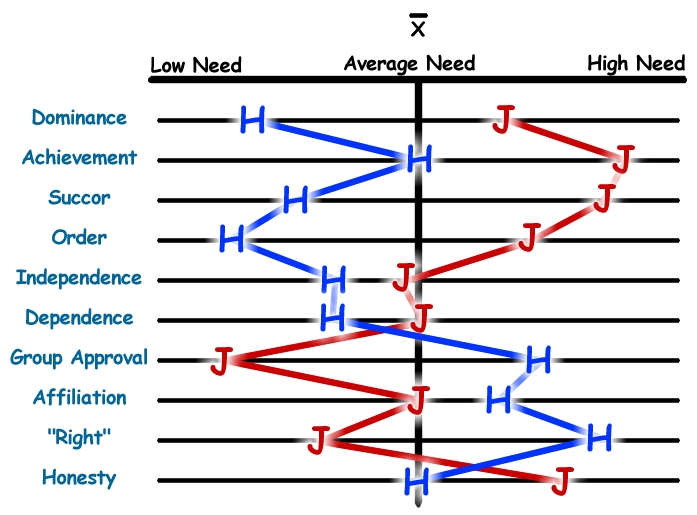

Now we'll introduce Jeff to the imaginary young woman we have had in mind for him, Helen. Let's overlay her zig zag on top of Jeff's.

Now let me ask you two questions. First, will Jeff and Helen get along? Second, is Helen's zig zag better than Jeff's or is Jeff's better than Helen's?

Answer to the first, no one can know. The second question is a non question and the best answer to a non-question is a non-answer. Neither is right or wrong, good or bad. Zig zags just are. They aren't good or bad, better or worse, best or worst. One unique zig zag by definition cannot be compared to all others and be found wanting.

Let's look at some possible results of putting Jeff and Helen together. How might their zig zags interact?

Jeff invites Helen to a fraternity party and she accepts. He tells her, "I'll pick you up at 7pm."

Jeff gets to her dormitory at 6:30 in the evening and calls Helen's room. Her roommate says, "Oh! Hi Jeff. Helen just got back from a volleyball game and has jumped into the shower. She'll be ready in a few minutes."

"Fine," Jeff says looking at his watch.

A few minutes pass. A few more pass. Jeff starts to perspire and pace the lobby. He keeps looking at his watch and starts to get more than a little annoyed. As he watches other couples coming and going and his frustration builds. He looks at his watch one more time as if he could slow the second-hand and stop the minutes from hurrying into history.

Seven o'clock comes and goes. The clock creeps up to 7:15 and still no sign of Helen. At 7:45, Helen comes down and greets Jeff with a grin and says, "Sorry I'm running a little late. But I remember you saying you'd pick me up at seven-thirty. How's it going?"

"No, I said seven."

"I distinctly remember you saying 7:30. I know because I recall thinking that I would have plenty of time to get back from the volleyball game before you got here. And even if I was late, I wouldn't be too late."

Jeff holds back his temper and says, "Well, you're probably right. Shall we go?"

Helen says, "Sure," as she starts to remember that Jeff did say 7pm. She thinks to herself, why admit to being wrong, he doesn't need to know that.

Jeff is angry, mad, frustrated, annoyed, and a bunch of other choice emotions. From this point anything could happen. But what was going on up to now with Jeff and Helen.

In your mind, what do you think of Jeff? Is he an over- regimented person who doesn't care what Helen does as long as she does it on time? Is he an impatient bastard or a pitiful clock- watcher? Just what is Jeff's problem with being a few minutes late? And doesn't Jeff care about being told he has a poor memory in so many words?

What about this Helen woman we set Jeff up with? What kind of uncaring, selfish human being is she? Doesn't she realize other people could be depending on her? Is she some kind of manipulative hag who would lie to someone to weasel out of any bad situation?

Though we know better than to assume that we know exactly what is going on with Jeff or Helen, we can at least begin to analyze their behaviors and emotional reactions in light of their unique zig zags.

First, Jeff's high need for order and predictability drove a number of his behaviors and responses. He showed up early so he wouldn't be late. He feels fine when he knows what will happen when. As soon as things get a little unpredictable, Jeff gets anxious and nervous. When Helen appeared to be violating this component of his sense of self, he became agitated: perspiring, pacing, watch-checking, and emotional turmoil.

In addition, his high need for succor contributed to his frustration. He always gets a gnawing feeling that if he shows up late for something, he sends the message to the people waiting that they are not important nor deserving of courtesy and concern. If he is seen as less than a person who cares, he has no choice but to punish himself with anxiety and guilt. This is the childlike nature of learned needs operating in his zig zag. It's as if a little voice is saying in his ear, "I will not consider you worthy if you do not behave as a person who cares," and that little voice is his own.

Consider what Jeff did when Helen said she was sure he had given her another time. Even though he was sure of the time he told her, he didn't feel being right was nearly as important as getting to the party on time. His need to be right just isn't that powerful.

What was Helen up to? As compared to Jeff, her need for order is very low. She didn't think it was so important to be on time. In her way of being in the world, a few minutes one way or another really doesn't matter. It would not violate her sense of self to be late.

Her need to be right kicked into gear, too. She knew darn well Jeff had said seven-thirty. Even after she realized she was wrong she wasn't about to suggest that she could be wrong. Add to this her average need for honesty and we can see that it probably wouldn't bother her to "lie by omission". The situation wasn't life-threatening to her zig zag.

Are you ready to think about these two human beings a little differently? Is one a ogre and the other an angel? Is one a bitch and the other saint? Are both unreasonable? Would you have jumped to some of the earlier conclusions I suggested? Or would you have come up with your own brands for these two? It's very easy to jump to conclusions, isn't it?

All we can know about other people is what they say and how they say

it and what they do and how they do it. We can't know and we will never

know WHY people do what they do. Even if we have the luxury of peeling

back their behaviors and discovering their zig zags, we can't be sure of

the exact reasons people act this way or that. We can only guess. This

will always be our lot.

Next Page: How We Got The Way We Are-Part 2 Onion Skins