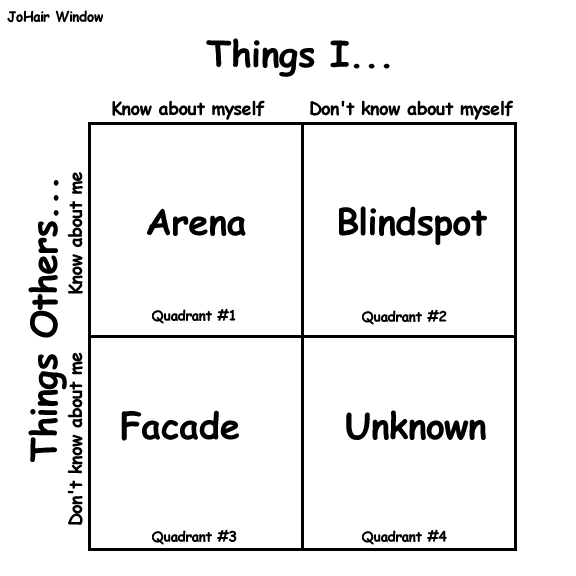

The model works like this. Picture a square window with four panes.

The two columns of panes are labeled "What I know about me" and "What I

don't know about me" and the rows are labeled "What you know about me"

and "What you don't know about me." The window looks something like this:

Quadrant 1, the pane in the upper left-hand corner, is called the Arena. This is the area in which both of us have the same information about me. This is the area of free and open communications. Here, both of us are aware of my behaviors and motivations, the things I do and say and the possible reasons why I do and say them.

Quadrant 2, the pane in the upper right-hand corner, is called the Blind Spot. This is the area in which you have information about me of which I am not aware. You have control over the information in the Blind Spot. Unless you share the information with me, I cannot know how I come across to you. Dr. Timmons also calls this the B. O. Area. It is as if I have a very strong body odor and everyone else knows it, but me.

Quadrant 3, the pane in the lower left-hand corner, is called the Facade. This is the area in which I have information about me that you do not have. This area is under my control. You cannot know this information unless I share it with you. Some of the information which you would not know about me might include my past behaviors, my motives, knowledge I might have, and intentions towards you. Here, my hidden agenda resides.

Quadrant 4, the pane in the lower right-hand corner, is called the Unknown. This is the area in which information about me is not known to you or me. Neither of us have control over this area. The information in this area may be discovered through insights after repeated and indepth interactions with you or through facilitation from a third party. I could go to a psychotherapist or psychoanalyst to find out information in this area, but in terms of day to day interactions, this information is generally not needed.

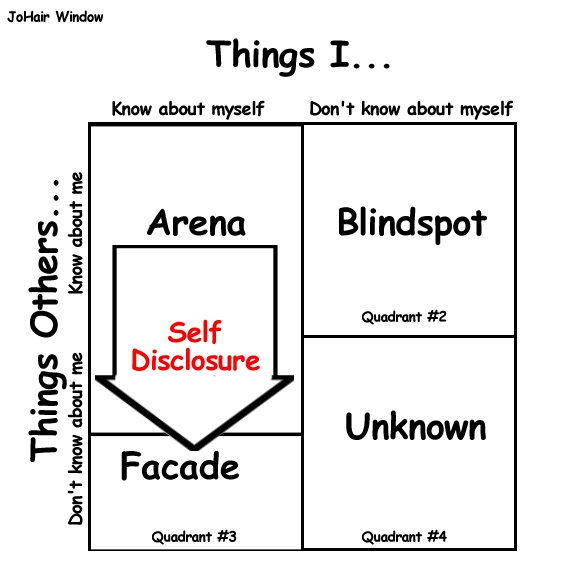

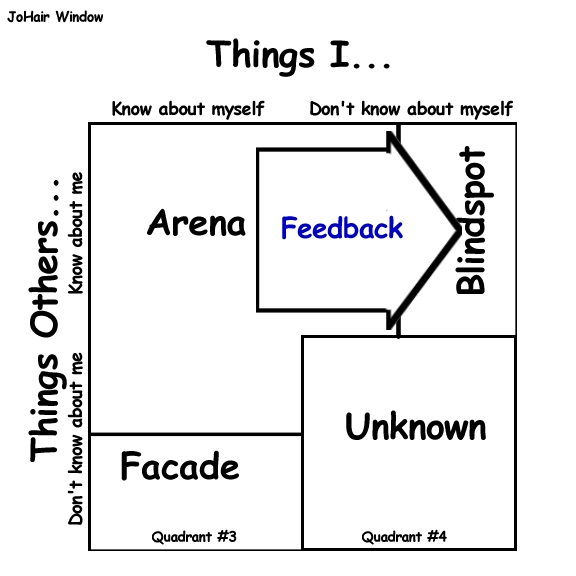

To increase the flow of free and open communications and improve the effectiveness of our relationship, the Arena between us must increase in size. There are two ways to increase the size of the Arena. The first way we can enlarge the Arena between us is for me to reduce my Facade. I control whether or not I share information about me with you. I also control what kind of information and how much information I let you know. The more information I share with you, the less you have to guess about me. As a result, our communications improve because you will have more data with which to work.

Secondly, you can share information about me over which you have control. This information is in my Blind Spot and I cannot know about it until you give it to me. By reducing my Blind Spot, the Arena increases in size. Our communication will also improve because I will have more data with which to work.

The first approach to enlarging the Arena is called sharing or self-disclosure; the second is called interpersonal feedback.

Information we can share about ourselves

Sensing- I can share with you the information I am receiving from my senses. My senses are always being bombarded by data from the environment. I may perceive these data differently than you. For instance, I may find the temperature in the room too hot, whereas you are perfectly comfortable. It could be important to our interaction for me to share with you how I sense the temperature in the room. The temperature may be distracting me from paying complete attention to you. If I say, "I notice that it is very warm in this room and I am sweating up a storm," we might decide to move to another room or adjust the thermostat. Sharing what my sensory organs are picking up may be useful information from my facade.Thinking- I can share with you my thoughts, ideas, and opinions. I can let you know about what I know and what I believe and how I make sense of what is going on. I can tell you how I organize my thoughts. For instance, if we were working on a task together that I had done hundreds of times before, it would probably improve our interaction if I let you know this.

Feeling- I can share with you my emotional state. I can let you know if I am angry, happy, sad, mad, pleased, confused, comfortable, and the whole range of emotions I am experiencing in my interaction with you. For instance, you might work with me differently if I told you that I get upset when people look over my shoulder while I am working on a task. If I didn't tell you this, you would have no idea why I acted annoyed everytime you stood behind me.

Needs- I can share with you the things I need, want, and expect. I can let you know what it will take to satisfy me. I can tell you how I would like to be treated. I may be exposing my vulnerability by telling you what I need. But I may find that you have the resources to help me out. You have little chance to satisfy my needs if you do not know what they are.

Actions- I can share with you what I have done, what I am doing, and what I am about to do. I can also share with you the reason for my actions and give you some insight into my motives. If we are sitting at a table and I suddenly get up and walk out of the room, you have to infer what I am up to. However, if I tell you that I have to go to the restroom and will be back in a few minutes, you don't have to guess as much about what I am doing.

Sharing is under the discloser's

control

In an interaction with you, I choose whether or not I will share information about myself with you. I am in control of my Facade and no one else can make me share that which I do not want to share. Likewise, I cannot demand that you share information from your Facade with me. To be most effective, we must allow others to decide whether or not they wish to share. We violate others' sense of self when we pressure them to share information with us they may not want us to know.

Risk

If our goal is to increase the free flow of information and improve open communications, we must share personal information with each other. I have to share information about myself with you. You have to share information about yourself with me. However, sharing is a risky business.

If I share information with you about myself, how can I be sure that you won't use it against me? If you expose your vulnerabilities to me, how do you know I won't hurt you and the people you love? I can never be sure you won't hurt me. Likewise, you can never be sure I won't violate you. But if we are to accomplish our goal, we have to take a risk and share. This means we have to have a trust relationship.

Trust

A trust relationship is many things to many people. In terms of the people stuff principles we have been discussing, a trust relationship means you and I respect one another's uniqueness and appreciate our needs to feel like somebody. We strive to enhance and protect each other's zig zags, try not to violate each other, and preserve each other's dignity. We have an unquestioning confidence that when we offer one another sensitive information about ourselves, we will not use the information to hurt each other.

Going First

Trust doesn't just appear. It has to be built slowly and carefully. One way to begin building a trust relationship is for me to share something with you about me. The first steps include taking a risk and sharing something with you first. You will be more disposed to share something about yourself with me if you see me go first. On the other hand, if I depend upon you to share first and withhold information about myself until you share, we may not get out of the blocks. If I am aware that sharing breeds openness and openness breeds trust, if I have a feeling you are not aware of this, and if our goal is to build a trust relationship, it is my responsibility to take the risk and go first. Going first doesn't guarantee that we will be on our way to building a trust relationship. However, not going first definitely guarantees that we will struggle in our efforts. If someone doesn't take a risk and share first, we may never know the joys of a trust relationship.

How much should we share

How much we share and what we share is important. We need to share only that information which will nurture our trust relationships. To share everything we can is probably not useful or wise. We could scare others off if we dump our life histories and every thought we have ever had into their laps. The information I share with my wife will be much different and a lot more than the information I share with my friends. The data and inferences I share with my friends will be different in volume and type than that which I share with my insurance person. The purpose and nature of each trust relationship I have governs what I share with others. In my opinion, each of us has to determine what and how much we share. However, as a general rule, the more we share, the more open and effective our relationships will be, the more trust we will build, the more others are likely to share with us, and the more joy we will have from our interactions.

When Dr. Timmons introduced the concept of interpersonal feedback to his classes, a student would invariably say something like, "Oh, you mean constructive criticism." Dr. T would smile and say, "Now, that's an oxymoron, a combination of mutually exclusive or contradictory words. For instance, civil wars, final research, or military intelligence." He would go on to explain that criticism means to analyze by breaking something into its parts while constructive relates to building. How can we build and break apart at the same time? Effective feedback is definitely not constructive criticism. It attends to the somebodiness of another, recognizes the uniqueness of that person, and seeks to enhance the other's sense of self. It attempts to honor a person by giving him information he cannot know without our help. Criticism is often seen as an attack. Feedback, the effective variety, is intended as a gift.

To help us give others feedback effectively, Dr. Timmons offered the

following ten guidelines based on the people stuff principles. They are:

1. Feedback must be solicited or agreed to.Following these ten guidelines improves the effectiveness of our feedback to others. They help us preserve someone's sense of self, reduce the threat to his or her zig zag, and maintain open lines of communications. Here's a look at each guideline, how it works, and why it's important.2. Feedback is my perception and my truth, not fact.

3. Feedback is concerned with specific behavior.

4. Feedback relates to behaviors under the control of the receiver.

5. Feedback should be given close in time.

6. Feedback can relate to either positive or negative aspects of behavior.

7. Feedback is non-judgmental.

8. Feedback is not advice.

9. Feedback becomes the property of the receiver.

10. Feedback, ideally, should be group shared.

Feedback must be solicited or agreed to. Though I am in control of the information in your Blind Spot, you have the right to request, accept, or refuse feedback from me. I must respect this right if I am to be most effective. To give you information about yourself when you do not want it or when you are not prepared to receive it, will not be productive or effective. I may violate your sense of self and you may perceive me as attacking the somebody you have got to feel like. You may feel you need to defend yourself if I offer feedback which is unsolicited or to which you have not agreed. Feedback that is laid on you without regard to your wishes does not promote openness and a free exchange of information.Feedback is my perception and my truth, not fact. The content of my feedback to you comes from the data I have gathered and passed through my perceptual filters, the inferences I have drawn about what and how you did and said something, and my personal emotional or physical responses to it. I cannot know how others see your behavior. I cannot know how others feel and think about your behavior. I can only know how I perceive what you say and do. This is all I can know and therefore, all I can share. Not only is it inappropriate, it is inaccurate for me to say something like, "When you do this, people don't like it," or "Nobody enjoys someone who does that," or "Everybody knows you shouldn't act that way." How in the world would I know? Feedback is my "truth", not anyone else's.

Feedback is concerned with specific behavior. How helpful would it be to you if I said, "I like the way you do things around here"? Would you know what I was talking about if I told you, "I get upset with the way you treat people"? You may enjoy hearing the first statement, but wonder to which one of your vast array of behaviors I am referring. The second statement may leave you confused and hurt and guessing what I meant. General feedback is not useful, because you have to infer which behavior or behaviors have caught my attention.

Is it more helpful to you if I were to say, "When you gave me that pat on the back just now, I really felt good about myself," or "When you said, 'You don't know what you're talking about', I sensed you were attacking me and I felt very defensive"? The more specific, I am the more efective I am in offering you feedback.

Feedback relates to behaviors under the control of the receiver. I have a habit of bouncing my leg rapidly which shakes the table and the floor and anything I am connected to. Frequently, I am not aware I am doing this. If someone lets me know it is annoying him, I can stop it. I do not have to bounce my leg. I can control this behavior. It is something I can do something about. But let's say the right-side of your face has a muscular disorder that causes your eye to twitch. You can't do anything about it. You have no control over it. And as much as you would like for it to stop, the twitch does what it wants. I come to you and offer you some feedback, "When your face twitches, I feel uncomfortable." How effective is this feedback? Not very, right? Dr. Timmons often uses the example of someone who stutters: "Fred, when you stutter, I feel very embarassed." The best Fred can do is say, "Ththththth thank yyyyyyou."

Ideally, feedback should concern behaviors people can control. There are times, however, when feedback regarding a behavior someone cannot control can be valuable. To let others know how their behavior impacts you may be useful. For instance, a young woman with a heavy Southern accent cannot control how she talks. She may feel very self-conscious about it. If I find her accent charming and attractive, I could dispel some of her uneasiness by sharing my feelings with her.

Feedback should be given close in time. Feedback about specific behaviors is most effective the sooner it is given after the behavior occurred. The specifics are clearer, the details more vivid, and the feelings engendered do not have to be recreated. It simply isn't effective to share information from history. How would you feel if I said, "Six months ago, you got up and left the living room in the middle of our conversation. I got annoyed about that."? Sounds like I'm holding a grudge or I am some kind of petty human being, doesn't it? The closer in time, the more effective the feedback.

Feedback can relate to either positive or negative aspects of behavior. Often people believe feedback concerns only the negative aspects and impacts someone's behavior has on us. Obviously, you won't have an opportunity to change the behavior I respond to negatively unless you are aware of how it comes across to me. Without the information, you have no choices. In the same way, you cannot repeat or continue a behavior which I perceive to be very positive unless you know about it. For instance, a friend of mine noticed that I picked up my plate after I finished eating when I visited his home. Just a little thing. He said, "Tom, I really appreciate it when you pick up your plate and bring it to the sink. You can come over anytime." Do you think I pick up my plate when I'm in his home?

Feedback is non-judgmental. It doesn't suggest that a behavior is a stupid, rotten, no good, and evil thing to do. It doesn't say that a behavior is the most wonderful, intelligent, and kind- hearted thing to do. Effective feedback does not include a value judgement. Rather, my feedback needs to avoid the rightness and wrongness issue and should focus on simply describing what the behavior appeared to be and how it affected me. Few people appreciate judgmental comments...evaluative statements often breed defensiveness.

Feedback is not advice. In order for me to give you good advice, I need to know all of your thought's and feelings. I would have to have experienced your experiences. I'd have to be able to read your mind. I would need to know all the issues involved in the situation about which I'm to share my vast and authoritative knowledge. And once I give you this valuable input, I would want you to agree to give me 100% of the credit if the advice works, but for you to accept all the blame if it doesn't. This is advice.

Feedback is not effective if it comes across as advice. It doesn't not suggest you should do this or quit doing that. Feedback which comes across as advice is not welcomed and does not promote open communications.

Feedback becomes the property of the receiver. Effective feedback does not imply that you should do something with the information I have given you. When I offer you feedback, I should not expect you to change your behavior for me. The goal of feedback is to enlarge the Arena between us, not change your behavior. You may change your behavior, but that is up to you. Feedback is like a gift. Once the gift is given, the receiver can do with the gift as he or she pleases. I, the giver, cannot demand that you do this or that with it. The gift is no longer mine.

Feedback, ideally, should be group shared. Without explanation, this guideline gives people a little trouble. "You mean to say when I give my spouse feedback, I am supposed to call the neighbors over so that they can witness it?" some have asked. The answer is no. In the case of spouses giving one another feedback, the group is two and the neighbors aren't and shouldn't be involved. In other cases, however, it will be more effective if when I give feedback to you about a specific behavior you get more information from others. I should encourage you to check out my feedback and ask for feedback from others who are impacted by the behavior. For instance, after I taught a seminar, one of the participants offered me some feedback. He said, "Your examples didn't help me understand what you were trying to say." We discussed this a bit and he left. I felt a mixture of regret, annoyance, and concern and I swung back and forth through these feelings the rest of the week. I ran across a couple of participants later in the week and asked them for some feedback about my examples. In their opinion, they thought the examples were great, that they vividly demonstrated the material I had given them. This feedback encouraged me and I felt more confident about sticking with my examples. Gathering more feedback from others regarding a specific behavior does not mean one needs to stand in front of an audience. It is quite enough to gather it in privacy and confidentially from one person at a time as close in time as you can.

Dr. Timmons' Famous Example to be inserted

Practice and "I" Statements

Learning to give feedback effectively requires a lot of practice. When I a tried it out the first few times, I stumbled and fumbled quite a bit. The targets of my feedback, luckily, were learning the same guidelines at the same time and we were giving each feedback for practice. We got a lot of feedback about how we gave feedback. This was a great way to learn and I would encourage you to do the same thing.

To help you in your quest to become more effective in your interpersonal relationships using feedback, here are some sentence stems or sentence starters. They are called "I" statements. "I" statements are constructed to send the message, "This is my perception and no one else's perception. I am responsible for how I feel about your behavior, not you. You can't make me feel a certain way. I choose how I feel and I can work on choosing to feel differently, but that is my concern."

"You" statements are statements which send the following message, "I am not responsible for how I feel about your behavior. You are the person responsible. I accuse you of yanking my chain and making me feel and think and perceive and behave and react the way you want me to. It is your fault, not mine." Some common "You" statements are "You make me...," "I hate it when you...," "People don't like it when you...," and "Don't you think..."

Notice the difference between the previous statements and the "I" statements which follow.

I get the feeling that...I sense that ...

What I see...

What I heard you say is...

You came across to me as... (Looks like a "You" statement; "to me" equals "I")

"You" statements deflect responsibility and tend to threaten the

persons to whom we wish to give feedback. If they feel threatened, they

become defensive. If the feel defensive, they tend to push us away. If

we are pushed away, our communications suffer, information is not exchanged

freely, and trust is destroyed. "I" statements are a technique which is

helpful if used genuinely and sincerely. Remember, our words and music

must go together if we are to be congruent. If we misuse "I" statements

and come across incongruently, our feedback will not be effective.

Learning about our onion skins, and possible zig zags and learned needs.

Next Page: How We Can Operate More Effectively- Part 2 Active Listening