Change:

Its Nature and Our Responses to

It

by

Tom Sylvest, Jr.

1992

THE NATURE OF CHANGE

Direction of Change

Rate of Change

Patterns Of Change

RESPONSE TO CHANGE

The Change Reaction

Characteristics of Change Influencing

Our Responses

Strategies to Prevent and Cope with

Change Effectively

THE

NATURE OF CHANGE

change v make something

different in some particular.

change n 1: the act, process or result of changing.

Understanding change has always been important. The human race is the result of change. The human race is affected by change. The human race affects change.

We need change. We pursue change. We like change. We dislike change. We prepare for change. We are stunned by change.

Change is a condition we take for granted. We proclaim, "The only constant is change," and think we are very clever. However, change is not an act, process or result most people understand with any great depth.

Understanding the basic nature of change is critical to designers and planners. Without this understanding, our plans will be ineffective. We risk planning actions for imagined future situations which bear little to no resemblance to the actual situations that result. It would be like exhausting one's resources buying only a summer wardrobe without recognizing seasonal weather patterns.

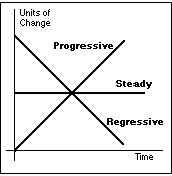

Our understanding of the nature of change is essential. Change has direction, rate and pattern.

Change over time can have direction. It may move progressively; each change reaches higher, better, or more advanced levels. Technology, the world's population, and the number of persons in poverty have progressed over time.

It may move regressively; each change reaches lower, worse or less advanced levels. Deaths from some diseases, the number of union members, and the demand for cassette tapes have declined.

Change over time may also move in

a steady fashion with no discernible direction.

Another characteristic of change is the rate at which it occurs over time. Accelerating change means the frequency of change increases with each passing time interval.

Change may decelerate; as each time period expires, fewer changes happen.

The rate of change may also be constant. Planning for the future requires us to discover the rate of change in our environment.

Effective planning in a changing environment depends on our understanding of the patterns of change. Understanding the pattern of change, in addition to the direction and rate of the change, enables us to design more appropriate responses for the future.

There are four basic patterns of change: erratic, gradual, sudden, and periodic. Erratic change lacks regularity, consistency, and uniformity. It is difficult if not impossible to predict future conditions in an environment experiencing erratic change. An effective strategy to deal with this type of environment is to measure the range of change, the peaks and valleys, and plan responses for points within the range. One example of an environment of erratic change is the day-to-day value of the Dow-Jones Industrial Index.

Gradual change occurs in slight and even imperceptible degrees. We may not even recognize the change until much time has passed. The erosion of mountains, the movement of continents, and the position of our galaxy in the universe are all examples of gradual change. The danger of gradual change is that we may not respond to it until it is too late. We may feel confident that we have plenty of time to respond. We may even deny that change is occurring because it is so gradual. Gradual change environments need monitoring systems designed to magnify the incidents of change and recognize unusual movements. i.e. laser measuring devices along the San Andreas Fault.

Sudden change is unexpected, abrupt, and occurs in a very short time frame. When this type of change happens, elements in the environment are not prepared and they do not have enough time or resources to develop immediate responses. Sudden change can be beneficial as in winning a lottery or the introduction of a technology. This type of change can be quite devastating to the elements in an environment as well; a tornado destroying one's home or a collapse of confidence in money markets.

The fourth pattern of change, Periodic, occurs and recurs at regular intervals of time. The most familiar example of periodic or cyclical change is that associated with the changing of the seasons. Temperature ranges, basic weather patterns, precipitation levels, the angle of the sun, and the position of the constellations can be predicted because of the periodic pattern of change associated with the position of the Earth in its orbit. Systems can construct very specific and detailed responses to periodic change within an environment.

All environments experience change. All elements within environments experience change. Planners must discern the direction, rate and patterns of change in their environment. Understanding the patterns help planners design appropriate responses to prevent change, defend against change, cope with change, benefit from change, influence change, control change, and even create change.

RESPONSE

TO CHANGE

Change is not necessarily a problem

for us. When it is a problem, it certainly isnít because we have

a hard time defining what change is. Change is simply something that

is different in some way. The dictionary definition of change is

the act, process, or result of making something different in some particular

way. By this definition, change is not a new phenomenon. We

have been working in environments of change our entire history on this

planet. We have even welcomed change and caused it. In general,

most of the change we face we handle just fine.

What is new about change is its dynamics. These dynamics have changed the face of change forever and have urged us to look at change in new and different ways. The first dynamic is the accelerating rate of change; the second, our awareness of it. Both of these dynamics, not surprisingly, stem from a change...technological changes in gathering, generating, interpreting, and communicating information. This increases the speed at which we exchange, use and make decisions based on the information.

Change will continue to accelerate and we will become more and more aware of it as it is happening. Some changes will affect us and some will not.

![]()

When change occurs, something that was familiar is now different or something which never existed has now appeared. When something is different, our past knowledge about the thing that changed may no longer apply. We question the validity and reliability of the information we had about the object of change. We wonder whether or not we have the capacity to deal with this new thing. We are uncertain of the meaning of the change. We automatically ask ourselves many questions, including: Will the change affect me and those I care about negatively or positively? Why has this change happened? Who is responsible for this change? What am I supposed to do about this change?

In the case when the change is something altogether new, suddenly appearing in ourselves or the environment, we donít have a readily available reference point from which to evaluate the change and what it means to us. We ask many more questions when this type of change occurs. In general, these are natural responses to change. We call these responses a condition of ambiguity.

Ambiguity is a condition of uncertainty and unpredictability. We do not know what something means and our capacity to deal with the situation comes into question. In addition, we are at a loss to predict if the meanings we place on the events and if the actions we take in reference to the change will be productive and effective. Any change of which we are aware leads us to a condition of ambiguity.

This ambiguity leads to anxiety. Anxiety or anxiousness is an uneasy feeling of pain and apprehensiveness regarding an impending or anticipated ill. When we are uncertain, when we cannot predict what will happen (to us) with any confidence, we have a tendency to label any change as negative. We will hold to this definition until something or someone proves the change to be positive to us. Until that time, we experience anxiety. This anxiety is a fear without a focus; there is no object to which we can direct the distressful and uneasy feelings. In effect, we fear what we do not and cannot know. Other feelings associated with ambiguity and anxiety include frustration, disappointment, stress, confusion, and feelings of unfairness.

Finally, anxiety leads to defense.

Because of our tendency to label change negatively until it is proven otherwise,

we must guard ourselves from the possible threat it poses to us.

We automatically construct defenses we hope will keep the ill from attacking

and hurting us. Our defenses, the things we say and do, we have learned

honestly. We use them time and again in the face of change because

they seem to work for us consistently. But generally, these behaviors

only work in the short-run, prevent us from gathering the information we

need, and divert our energies from appropriately adapting and adjusting

to the changes.

Here is a list of common defense

behaviors used to protect ourselves when people or situations change.

Most often these behaviors are ineffective and unproductive in the face

of change.

Anger

Over Questioning

Finger pointing

Blaming

Hiding

Resisting

Attacking

Counter-attacking

Ignoring

Tough and Ugly

Poor Mouthing

Accepting

Defending without Knowledge

Throwing Tantrums

Sabotaging

Withholding Info

Challenging the change

Avoiding

Malicious Obedience

Characteristics

of Change Influencing Our Responses

This ďChange ReactionĒ always occurs and cannot be avoided when we find ourselves in a situation in which the people and environment become different. Sometimes the process happens quickly, so fast we donít even notice the change, ambiguity, anxiety, and defensive behaviors we experience and use. A few times the process is so overwhelming we find it difficult to cope and literally think and feel we may cease to exist.

Obviously, not all change affects us the same way. We welcome some changes when it is to our benefit and ignore those changes which do not appear to cause us problems. Sometimes we are completely unaware of changes and do not respond at all. And there are times when we are the instigators of change.

Change only causes us concern when we are aware of it and certain characteristics of the change are operating. These characteristics are the number of a changes, the importance of the changes, our physical and psychological condition in the midst of the changes, our control or participation in the changes, and our competency regarding the changes. All of these characteristics of change are operating simultaneously as we try to define what a change means and how it will affect us. Hereís a review of how each of these characteristics increase the influence a change has on us.

Number of changes: We certainly can handle many changes over time. But when many changes occur at the same time or close in time, any one change, though small, can be enormous in its affect. Few of us can attend to two or three or four events at the same time. We are not equipped biologically, physically, or psychologically to handle but a limited amount of input. Too much change and too many changes close in time can overload our capacity to cope.

Importance of change: One very important change can elicit the same response as a many small changes happening at the same time. A positive or negative change increases in its importance to us when its threat to our status quo is great, it tremendously challenges the way we have typically operated, it causes us to dramatically change how we think, feel, and act, or it denies us resources we have come to depend upon.

Physical or psychological condition in change: Even small changes or few changes are difficult to cope with when we are operating physically and psychologically below par. If we are sick or emotionally distressed, we do not have all of our resources available to deal with a change in our situation. When change occurs, our already diminished and limited resources devoted to our healing may be over-taxed. This can increase the ambiguity and anxiety we feel and cause us to react more defensively.

Control or participation in change: Changes which we have some control over or in which we have a degree of participation do not impact us as strongly as change in which we have no say. Arbitrary changes and changes instigated from outside sources always increase the uncertainty and unpredictability of the situation. The greater the opportunity we have to influence the course of change and influence the changeís effects, the less anxious and defensive we feel.

Competency regarding changes: If we do not have the skills and knowledge to effectively deal with a change, we will experience more ambiguity and anxiety and become more defensive. Change often means we must do something different. When we donít know what to do, how to do it, and why to do it, a change will be difficult for us.

Strategies to Prevent and Cope with Change Effectively

Most of the time we react instinctively to change. We do a split-second cost-benefit analysis, assess the risk and odds of actions with no information, and guesstimate our energy consumption on the road to fighting or coping with the change. The ďChange ReactionĒ and the Characteristics of Change offer us clues to what we can do to more effectively deal with changes we face as individuals and as organizations of people.

Definitions:

Clearly define the change with which you must deal. With a clear

definition and the possible positive and negative impacts of the change

assessed, effective actions can be devised and taken to maximize the benefits

and minimize or eliminate the costs of the change. Some issues to

consider in defining change are:

Amount of Change- How much change is going on to which you must pay attention?MAD Test (Does it make a difference?)- Ask yourself and others affected by the change how important it is to your activities. How much influence and impact will the change have on what you do or may have to do?

Control, Influence, and Participation- Changes range from those you can absolutely control to those you have no control or influence over. By deciding whether a change is one you can control, participate in, or influence, you can determine where your resources would do you the most good.

Resources:

To prevent undesirable change, cope with unexpected change, and instigate

positive change, we must have the resources to get the jobs done.

A lack of sufficient resources can be detrimental to the capacity to handle

change of any sort. On the personal level, our physical and psychological

condition must be good. We can improve our abilities in this regard

through healthy lifestyles and learning more coping behaviors. On

both the personal and organizational level, we must have enough time and

money to effectively handle change. If we donít, we have to accumulate

these resources. How much is required can only be estimated.

Risk Tolerance: The uncertainties inherent in change cause us to make decisions in an atmosphere of risk where the odds arenít known. The more we can tolerate risk which means we can absorb some losses, the better we can face the risks. Without knowing the probabilities of winning and losing, we must be willing to make decisions and accept the consequences of the decisions. If we have sufficient resources, negative consequences can be handled.

Information: The more information we have, the less the uncertainty under which we must operate. This also lowers our anxiety. In addition, information can improve our ability or competency to handle change. General research and education about markets, societal influences, new developments, principles and techniques of living systems, and othersí responses to change improve our competency. In addition, we can learn specific skills required to deal with the new elements of work the change requires. Finally, we can network with others who find themselves in similar circumstances, are the instigators of change, or have influence on how the change will occur.

Act and Evaluate: After the change is defined, the resources are accumulated, your tolerance for risk is assessed, and the information is gathered, you must act. This entails selecting an appropriate response and setting a standard to determine how well you are achieving your results. As you take your actions, it is important to measure your actions and evaluate their results to be prepared to adjust as new circumstances emerge.

These strategies do not differ from

person to person, organization to organization. The individual tactics

each of us use will be unique to us and our groups, however. The

main reasons for this vary because of the ways we define the change, evaluate

it, use our resources, gather information, tolerate risk, and act.

The general approaches or strategies are similar to those

we use in management...planning, organizing, executing, and controlling.

In this respect, things havenít really changed at all.