HOW WE INTERACT WITH ONE ANOTHER-

DATA-INFERENCE-PROPHECY

The

Questions We Must Ask

Few days go by that we don't rub up against other people. As they approach

us or as we come towards them, we consciously and unconsciously ask ourselves

the following questions.

Will they satisfy our learned needs or not? Will they supply or deny

us the resources that will help us reach our goals? Will they act as barriers

to our objectives or will they remove the obstacles in our paths? Will

they threaten our zig zags or will they help us feel like the unique somebodies

we've got to feel like? Will they threaten our senses of self or help us

preserve the persons we need to be? Should we ready our arsenals of defense

mechanisms or prepare our coping behaviors to bring them to us? Which onion

skins will we have to put into play to protect or enhance our selfs? What

will they do and say and how will they do it and say it and how will their

behaviors impact my well-being?

It is impossible to avoid, ignore, or escape these questions. I will

repeat, it is impossible to avoid, ignore, or escape these questions. In

some form, these questions are asked by us all. In all situations, we are

anxious for the answers. If we had the answers to these questions in each

and every situation, we could choose appropriate behaviors and be the most

effective human beings we could possibly be. The answers to these questions

would make our interactions with others predictable. If we had this predictability,

we could reduce our angst.

The

Answers We'll Never Get

As impossible as it is for us to avoid, ignore, or escape these questions,

it is just as impossible for us to know the answers. What can we know about

anyone else? Not much. We cannot know their zig zags, learned needs, self,

or the somebodies they have got to feel like. We cannot know why they do

what they do. We cannot know their motives, the reasons they behave in

certain ways, or what they will do next (to us). We cannot know their purpose,

what they mean, and what they are up to.

To be effective in our dealings with others, we need to know these things.

We need to know their motives, purposes, meanings, truths, and reasons

for what they do. We need to know what they are likely to do next. But

we can't.

All we can really know about others is their behaviors: what they say

and do; and how they say and do it. We can know nothing more. Generally,

this is not enough for us. Just knowing what their behaviors are is not

nearly as useful as knowing the reasons for their behaviors. How can we

find out what we cannot know. How do we make sense of what is going on.

The

Chasm of Understanding

We forever stand on the edge of a great chasm between what we really

know about others and what we need to know about others. This chasm is

very wide. This chasm is very deep. To interact with others, we need to

cross it.

To get to the other side and try to know what we can't, we must infer.

We leap the chasm with inferences about what people do and say and how

they do and say it. We have no choice but to infer. Our inferences provide

us the answers to the questions we cannot avoid, ignore, or escape. They

offer us the predictability we so desperately need when we interact with

others. And like our questions these inferences are impossible to avoid,

ignore, or escape.

To get to the other side and try to know what we can't, we must infer.

We leap the chasm with inferences about what people do and say and how

they do and say it. We have no choice but to infer. Our inferences provide

us the answers to the questions we cannot avoid, ignore, or escape. They

offer us the predictability we so desperately need when we interact with

others. And like our questions these inferences are impossible to avoid,

ignore, or escape.

Of all the principles of human behavior I have learned, this principle

is the most powerful I have come upon. It permeates everything we do and

say. It is how we operate with others. It is how we make sense of the world

in us and around us. It applies to all people regardless of culture, upbringing,

education, economic conditions, and geographic locations. It is a source

of pain and joy in all of our lives. If by some magic I were allowed to

give people one thing that would help them live in peace and harmony, this

is the principle and process I would want them to understand and use.

Here we'll look at the process, examine each component and its features.

We'll also explore some common examples of the principle at work and identify

the problems and opportunities the process offers us.

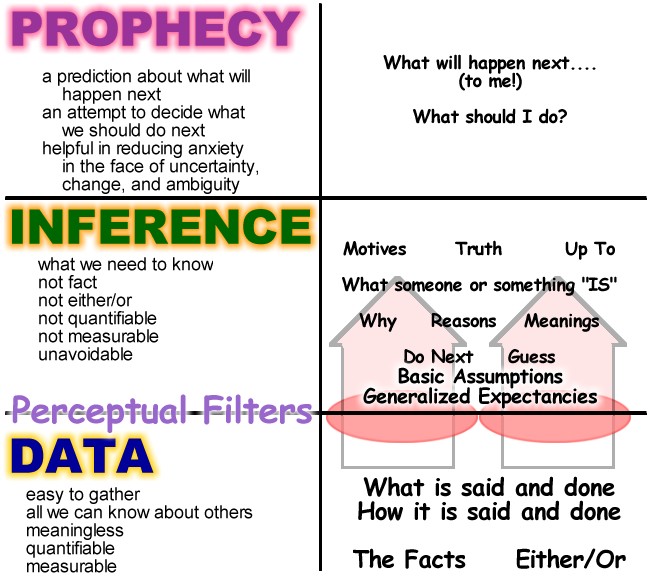

The

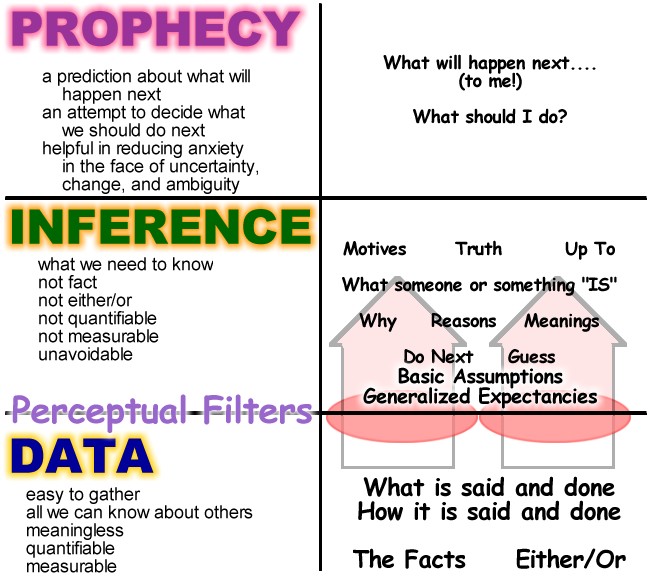

Data- Inference-Prophecy Process

The process of Data-Inference-Prophecy (DIP) is really rather simple.

We gather data, make inferences about the data, and based on those inferences,

come up with a prophecy about what will happen next. These are the three

levels all of us use to make sense of the world and communicate with one

another.

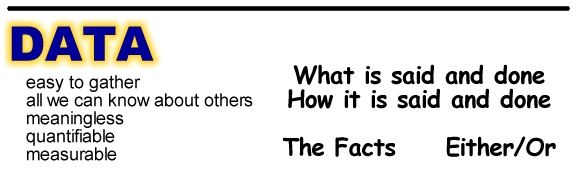

Data

Level

Earlier I stated, "All we can know about another person is what he

says and does and how he says and does it and nothing more." This is the

data with which we make our inferences.

A number of features define the nature of data:

A number of features define the nature of data:

-

Data are generally easy to gather. We use our senses to pick up the data

that is out there in the world. We are always gathering data. In fact,

it is almost impossible for us not to gather them. The primary reason data

is so easy to gather is because we need data in order to survive. If data

were difficult to gather, our lives would be in constant peril. Consider

a person who is blind or deaf; he or she needs some sort of assistance

in gathering the data that are necessary for existence. The assistance

they receive may come from others or a heightened capacity of their other

senses.

-

Data are the facts of a situation. The facts are the things that are done,

the actions that actual take place. We can describe facts very accurately

with a high degree of precision.

-

Data are what is said and done and how it is said and done. In terms of

human interactions, the most important facts we gather are the behaviors

of ourselves and other persons. The behaviors are either nonverbal, physical

body movements or verbal communicative performances.

-

Data are either / or in nature; either someone did something or said something

or she did not. The data we have gathered either happened or they didn't

happen. We have no question about the occurance or nonoccurance of data.

-

Data are generally agreed upon when witnessed by others. On the data level,

when two or more people with an equal capacity to gather data see or hear

something happen, they can always agree on what happened. They may not

agree to the meaning of what happened and they may interpret the data they

received differently, but the essential facts of the situation will be

the same for all of them. If you and I see 20 people in a room with their

hands raised, we will easily agree that we see 20 people with their hands

raised. If we asked an Aaskan eskimo, an Indian guru, and a Chinese general

to look upon the same scene, they will agree with us that 20 people have

their hands raised.

-

Data are quantifiable and measurable; you can count them and compare them

to some ruler. In the above example, we can count the number of people

in the room. If we have a predetermined amount in mind for this particular

group which defines a quorum, we are able to calculate and measure how

close or how far the number we see is from the quorum number. We can also

quantify and measure just how high the people have their hands raised.

We may use their shoulders as a reference point and measure in inches or

meters the distance from their index fingers to their shoulders.

-

Data are meaningless; they simply are until we put meaning to them. Data

by themselves do not tell us the reasons they exist. Until we place the

data in some context and relationship, they have no meaning.

-

Data are all we can ever know about other people. Here, 'know' means to

have 100 per cent certainty of what has happened and to be able to describe

it with unambiguous terms.

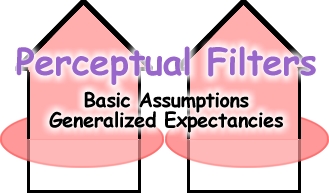

Perceptual

Filters

After we have gathered them, the data pass through our perceptual filters.

These perceptual filters are our basic assumptions and generalized expectancies

we acquired from our experiences. If you grew up in a nuturing, helping,

and caring environment and were taught that people were basically good,

you may have developed rose-colored filters. These filters would color

the data you gather. You would tend to see something someone does and says

as being positive. On the other hand, you may have grown up in an environment

that taught you to be wary of people, that things are no good, that you

can't be too careful, that you had better not trust anyone, or that people

are "out to get you." Your filters would tend to color the data you gather

negatively. Perceptual filters are the reason that when two of us witness

the same data and agree on what happened, we may not agree on what that

data mean.

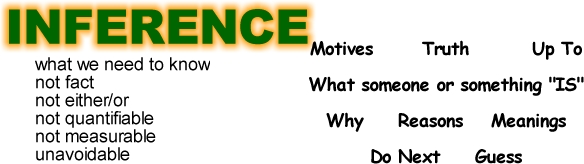

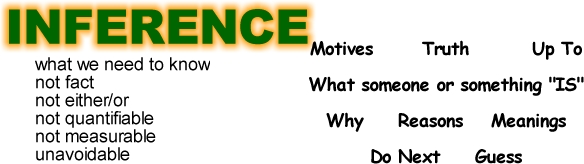

Inference

Level

Once we have gathered the data and they have passed through our filers,

we have no choice, but to make sense out of the data. In effect, we ask

ourselves, "What do the data mean?" We answer this question with inferences.

Inferences are very different from data. They are only guesses, maybe

educated guesses, but still guesses about the data and their meaning. Here

are the features that distinguish inferences from data.

-

Inferences are not facts. Inferences are our attempts to explain the whys

of the data we witness. An inference is not actual. It is the result of

our thinking about the data.

-

Inferences are not either / or in nature; they are merely judgements or

evaluations about data. We often try to impose either/or thinking on the

inference level. Either Notre Dame was the greatest team in the nation

or it was not. Either Ronald Reagan was the best president of the United

States or he was not. Either Elizabeth Taylor is the prettiest woman who

ever lived or she is not. Either /or thinking on the inference level is

ineffective. The number of possible inferences that may be drawn from one

set of data are too numerous to use either/or logic.

-

Inferences are our attempts to attribute meaning to the data. Because data

have no meaning and we all have an average need for predictability, we

must give the data we see and hear a definition. Without making some sense

of what is happening, has happened, or might happen next, we would not

have a point of reference to determine the threats to our sense of self.

-

Inferences are our individual answers to the questions about another person's

truths, motives, feelings, emotions, purposes, and reasons for what they

do and say. Again, because we require some predictability, we strongly

need a point of reference. Therefore, we read motives into the actions

and communications we see and hear.

-

Inferences are not quantifiable or measurable; they are subjective. We

cannot quantify or measure motives, reasons, purposes, or truths. We can

use data to define these things, but our definitions are still arbitrary.

If we can agree that 20 is a very large number, we can say there is a large

number of people in the room. But remember that "20 is a very large number"

is an inference itself.

-

Inferences are unavoidable; we have to make them to make sense of the world

and people in it. Once again, the reason we form inferences is to lessen

our anxiety and provide ourselves with predictability. If we did not form

inferences, we could place ourselves in great danger. Inferences are part

of our survival system.

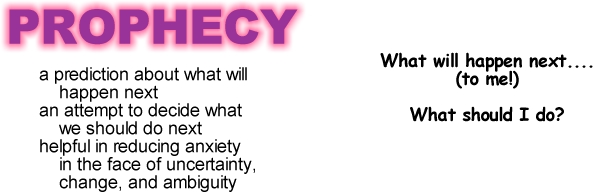

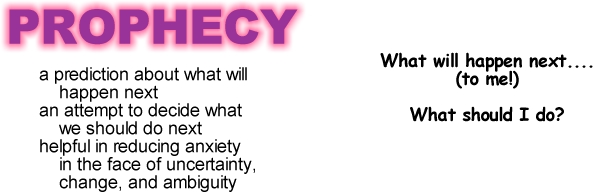

Prophecy

Level

All of us need some degree of predictability. So, after we have gathered

the data and made some guesses or inferences about the data, we predict

what will happen next. We make prophecies about others to help up deal

with them.

-

Prophecies are our predictions about what someone will do next.

-

Prophecies are our attempts to decide what we should do next

-

Prophecies are helpful in reducing our anxiety about a given set of circumstances

by giving us some degree of predictability.

Here's the DIP Graphic for easy reference:

Next Page: How We Operate-Part 2 Data-Inference-Prophecy Continued